I am currently researching early libraries in Perth to find out what was here before the State Library opened in 1889. It turns out, there was a fair bit, but you mostly had to pay for it. For example, in 1840, subscribers could join the Western Australian Book Society, where a case of books was ordered from England, lent out to members, then sold to make way for the next case of books (1). There was also a Church of England lending library in the 1840s, initiated by the author Rev. Hugh White of Dublin. He donated books he had written to form a library for “the benefit of the labouring classes” in the Swan River Colony (2). Others in the colony, including the Rev. J.B. Wittenoom, contributed, until there were 300 books on theology, science, history, biography, and travels. In 1846, the library was open on Friday afternoons, and books were loaned out free for a month (3).

However, the most important and widespread early libraries in Western Australia were part of Mechanics’ Institutes and other similar organisations, such as Working Men’s Associations (4). These aimed to offer “intellectual recreation and improvement” by providing a library, offering public lectures, and facilitating discussion groups (5). They were also seen as an opportunity to keep working men away from public drinking places (6). The first in the colony was the Swan River Mechanics’ Institute, established in 1851, then the Fremantle Mechanics’ Institute opened in 1852. Many others followed (7). Initially they were for men only, who had to be approved as members, and pay a subscription (8). As well as having library books for loan, newspapers and other periodicals were available in the reading room. In 1861, it was noteworthy that 32 books were borrowed on the same day! (9) Over time, the other activities dropped off, and the library became the most important part of the institutes. As a consequence, many were renamed Literary Institutes (10).

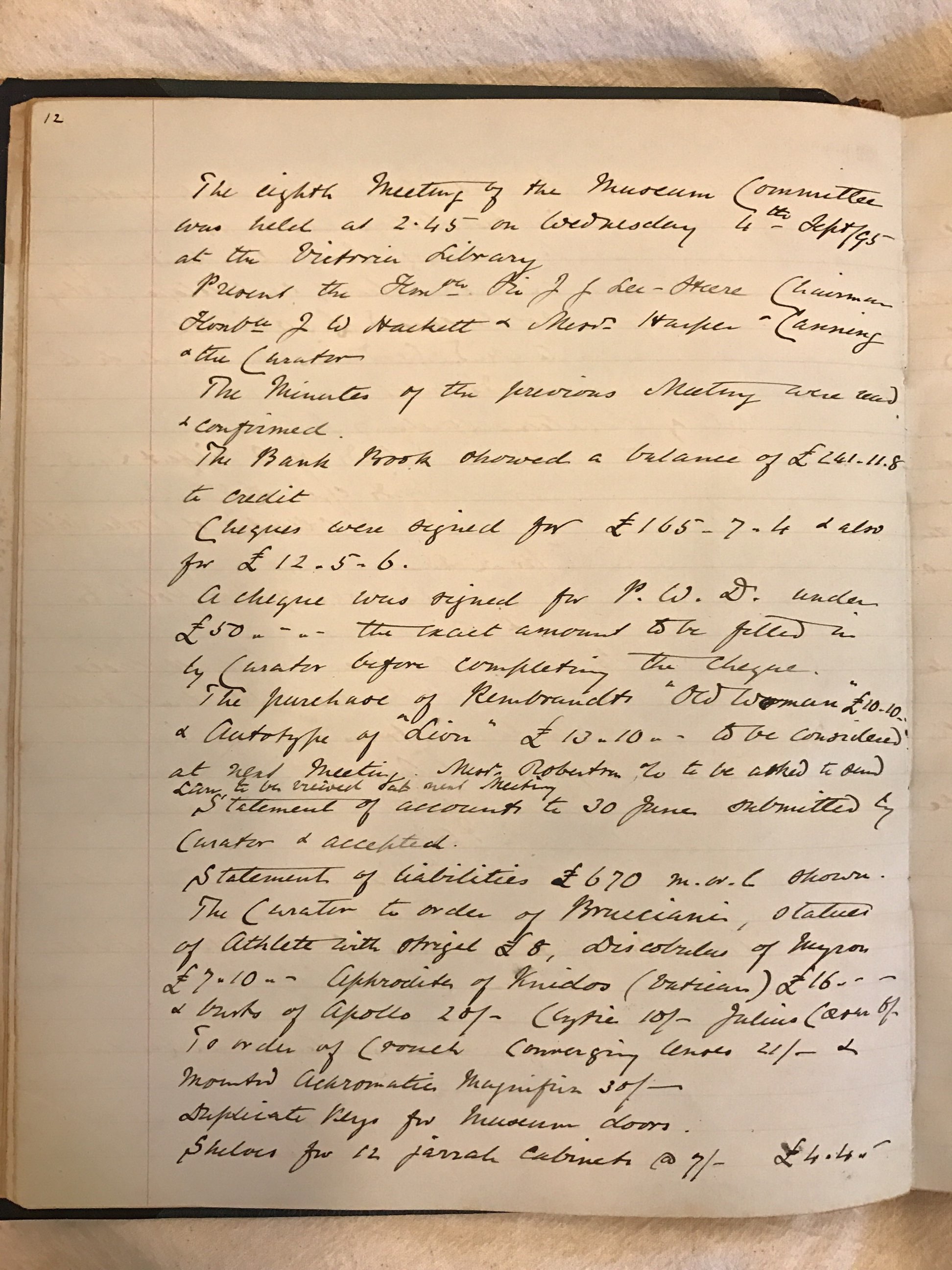

Recently, I have been looking at the minute books of the Swan River Mechanics’ Institute, which are now in the City of Perth Library. Renamed the Perth Literary Institute in 1909, the Perth City Council took over the library in 1957. The 1850s minutes contain decisions made in meetings, such as voting to allow particular men to join, getting bookcases made, and raffling old copies of the Illustrated London News. However, the most engaging aspect was the summaries of lengthy discussions on topics such as women’s intelligence, and spiritualism. It has been hard to tear my eyes away from these, but maybe not much has changed in relation to me and libraries!

[1] Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, January 18, 1840, 10. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article638823; “Western Australia Book Society," Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, July 18, 1840, 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page1644; "Swan River Reading Society," Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, August 29, 1840, 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page1668.

[2] "Report of the Committee of the Colonial Church Association [in Western Australia]," InquirerDecember 18, 1844, 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65583944.

[3] Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal August 8, 1846, 2. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article646878; "Report of the Committee of the Colonial Church Association [in Western Australia]", Inquirer December 18, 1844, 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article65583944.

[4] See for example "Ninth Annual Report of the Perth Working Men's Association," Perth Gazette and West Australian Times, 2 May 1873, 3. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3752303.

[5] “Swan River Mechanics’ Institute,” Perth Gazette and Independent Journal of Politics and News, 16 May 1851, 4. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3172474.

[6] Peter Rose, Wendy Birman and Michael White, “‘Respectable’ and ‘Useful’: the Institute Movement in Western Australia,” in Pioneering Culture: Mechanics’ Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, ed. Philip C. Candy (Adelaide: Auslib Press, 1994), 128.

[7] Rose, Birman and White, “‘Respectable’ and ‘Useful,’: the Institute Movement in Western Australia,” 139.

[8] Jo Darbyshire, Peruse: A History of the City of Perth Library 1851–2016 (Perth: City of Perth Library, 2016); Minutes of the Swan River Mechanics’ Institute, 3 May 1892, City of Perth History Centre Collection.

[9] Minutes of the Swan River Mechanics’ Institute, 1 July 1861.

[10] Rose, Birman and White, “‘Respectable’ and ‘Useful’: the Institute Movement in Western Australia,” 133-4, 136.

Banner image: Looking west up Hay Street, Perth, with Swan River Mechanics’ Institute on left and partially completed Town Hall on right, 1868. Photo courtesy of City of Perth History Centre Collection.

June 27, 2017